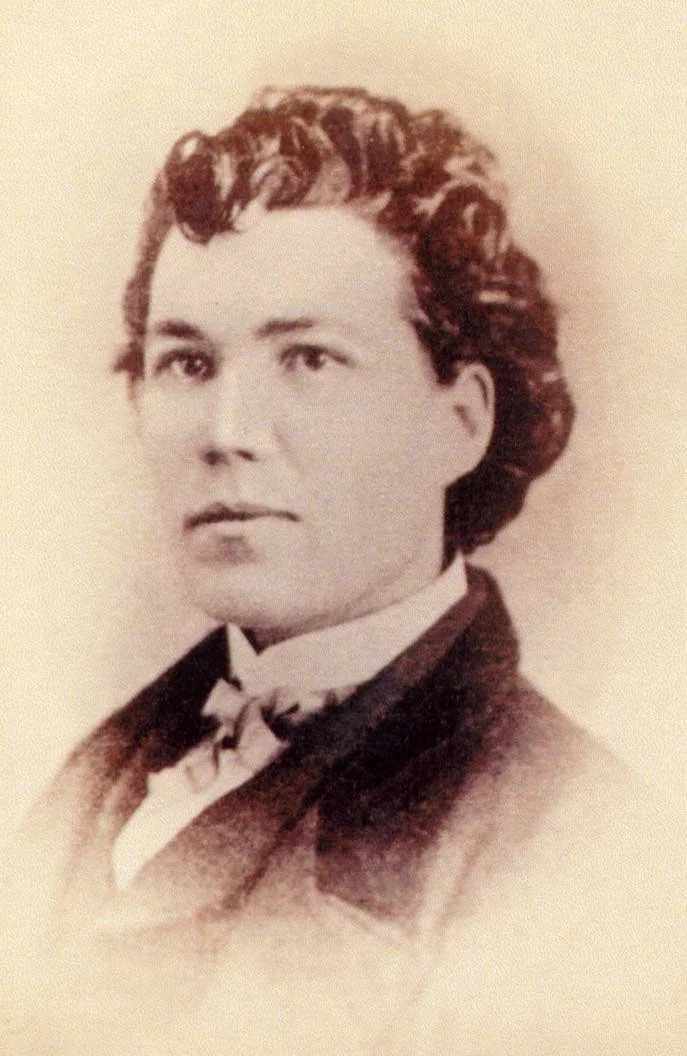

Sarah Emma Edmonds, aka Franklin Thompson

Sarah Edmonds, alias Franklin Flint Thompson

Sarah Edmonds as herself.

The New Brunswick woman who fought in the American Civil War – disguised as a man

During the American Civil, it was illegal for women to fight. Both the Union and the Confederate Armies forbade it – yet historians have identified over 400 women who disguised themselves as men and enlisted. One of the most famous of these women was Sarah Emondson, born in New Brunswick, Canada.

Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmonds (1841–1898), later known as Sarah Seelye, adopted the name Franklin Flint Thompson when she joined the Union Army. Her story is one of courage, deception, and an unwavering desire to serve.

Raised in a strict and abusive household, Sarah fled home at the age of fifteen with the help of her mother. She changed her surname to Edmonds to avoid detection and opened a millinery shop in Moncton. When her father tracked her down, she fled again – this time crossing the border into the United States.

To travel safely, Sarah disguised herself as a man. She found work selling Bibles door to door, a job that helped her blend in under the name Franklin Thompson.

On May 15, 1861, she enlisted in the 2nd Michigan Infantry as a three-year recruit. She served initially as a nurse and hospital attendant, but during the Battle of Williamsburg in 1862, she took up arms alongside her fellow soldiers and also acted as a stretcher-bearer, hauling wounded men from the battlefield for hours.

She claimed that she was also a highly skilled spy, keeping track of Confederate operations, disguised as a peddler, a lady, a maid or a slave. At one point she assumed the identity of a slave named Cuff, wearing a wig and painting her skin with silver nitrate and garnered valuable information that she was able to relay back to the Union side.

Franklin Thompson became known for undertaking risky missions, including acting as a mail carrier through enemy territory. On one such journey in August 1862, she was thrown from a mule and badly injured. The broken leg and internal damage would haunt her for the rest of her life and later became a key part of her application for a military pension.

In 1863, Sarah contracted malaria. When her request for leave was denied, she feared discovery if she sought treatment from army doctors. Instead, she quietly left – and Franklin Thompson was charged with desertion.

Once recovered and no longer in disguise, Sarah returned to service through the U.S. Christian Commission, working as a nurse from mid-1863 until the war’s end. In 1864, she published her memoir, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, and donated the proceeds to soldiers’ aid groups.

In 1867, she married Linus Seelye and had three children. Nearly a decade later, she attended a reunion of the 2nd Michigan Infantry. Her former comrades supported her appeal to have the desertion charge dropped — and helped secure her military pension. After eight years, she succeeded: in 1884, Franklin Thompson was cleared, and Sarah Edmonds received her pension.

In 1897, she achieved yet another milestone – becoming the only woman admitted to the Grand Army of the Republic, a Union veterans’ organization. She died the following year in Texas. In 1901, she was reburied with full military honours at Washington Cemetery in Houston. In 1992, she was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame.

Whether every detail of her story is true may be debated. What remains indisputable is that Sarah Edmonds was formally recognized by the United States government for her service in the Civil War – an extraordinary feat for a woman of her time.

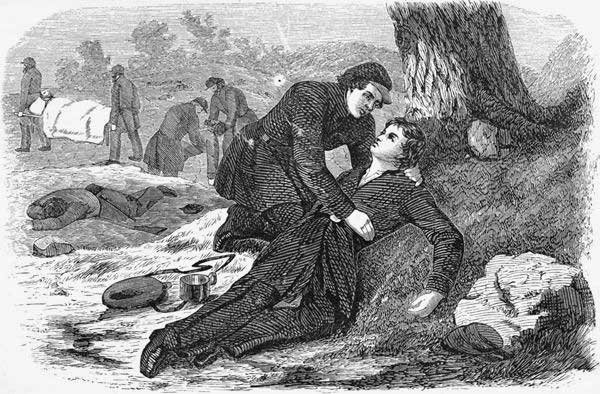

An Interesting Patient. Engraving from Sarah’s book, illustrating her aiding a wounded soldier who entrusts her with a secret. ‘I can trust you, and will tell you a secret. I am not what I seem, but am a female’.

It may seem impossible, but hundreds of women managed to hide their identities and serve in the Civil War.

Many passed as teenage boys – the army included numerous underage recruits, making slight builds and soft features less suspicious. Social norms at the time were so rigid that the simple act of cutting one’s hair, binding one’s chest, and donning trousers was enough to pass.

Recruits were rarely asked for proof of identity, and medical exams – if done at all – were often superficial. A firm handshake and a willingness to serve might be all it took.

Baggy uniforms helped hide female features. Some women adopted stereotypical male behaviours such as drinking, smoking, and swearing to avoid detection. And with the Union desperate for soldiers, many were accepted with few questions asked.

-

References:

American Battlefield Trust. (n.d.). Sarah Emma Edmonds. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/sarah-emma-edmonds

Illustration: Edmonds, S. E. (1865). Nurse and spy in the Union Army: The adventures and experiences of a woman in hospitals, camps, and battle-fields. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/38497

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, March 31). Sarah Emma Edmonds. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Emma_Edmonds

Sarah as a Women: National Park Service. (n.d). Sarah Emma Edmonds. https://www.nps.gov/people/sarah-emma-edmonds.htm